Actor Model in CosmWasm

CosmWasm (CW) is a popular smart contract platform for Cosmos blockchain ecosystem. It enables writing smart contracts code in Rust, which then gets compiled to Wasm.

In this post, I comment on CosmWasm’s concept of contracts as actors, one of the basic pillars of CosmWasm. There are interesting connections between concurrency (which is where the actor model originates from), Ethereum smart contracts, and the design of CW contracts as actors.

1. Concurrent execution

Concurrency is a model of execution where multiple computations run simultaneously. We can imagine a scheduler that decides on when each of the computations gets to make a couple of steps. The scheduler will make sure that each computation gets scheduled, but otherwise it can choose any interleaving of steps from different computations.

Is this a problem?

If the concurrent computations are fully independent, all is good. Things get more complicated if the concurrent computations have to collaborate.

Shared state

A common model of collaboration between concurrent computations is by sharing state. Assume x and y are two shared variables and observe the following concurrent computation:

x = 1; | y = x;

x = 3; | x = y * 2;

Assuming that initially x = y = 0, what is the value of (x, y) at the end of the execution? Depending on the ordering decided by the scheduler, it can be any of (6,3), (2,1), (0,0), and (3,0).

A typical way of dealing with the problem of many possible interleavings is by identifying critical parts of the concurrent execution and putting locks around it. Still, reasoning about different interleavings and locks is not easy. The difficulty arises from the fact that one thread does not know where in the execution is the other thread, and this ignorance is an important feature of concurrency.

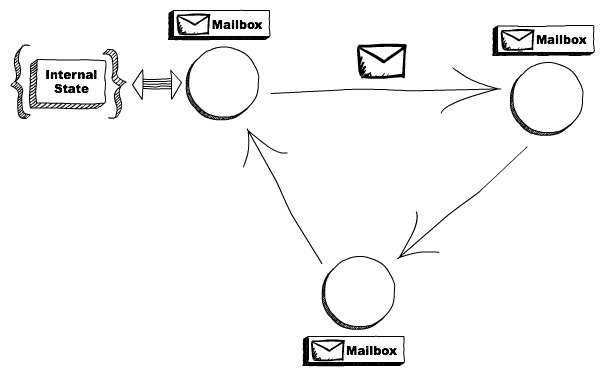

Actor Model

As a way to avoid the problems of dealing with shared state, a different programming model is proposed - the actor model. In the actor model, each computation is an actor, which can only access its local variables. The actors communicate by sending messages to each other, and their computation is triggered by messages received from other actors.

Each actor has its mailbox in which messages are stored. Typically, they are stored in the first-in-first-out fashion - this means that the order between messages by the same sender is preserved, but tells nothing about the order of messages sent by different senders. Upon receipt of a message, the actor 1) updates its internal state, 2) sends messages to other actors, or 3) instantiates new actors.

Because actors can only communicate by explicitly messaging each other and cannot access each other’s state, there is no need for locks.

2. Ethereum smart contracts

Smart contracts that run on Ethereum blockchain can be roughly described as sequentially run execution units that can call into each other. This is then typical sequential setting, right? Not quite. The problem is that the caller does not know what code a callee might run, and this ignorance brings it closer to the concurrent setting. (I learned about this perspective on Ethereum contracts concurrency from a very interesting paper by Sergey and Hodor, where they call the described setup uncooperative multitasking.) Viewing smart contracts that way, they resemble concurrent execution where each thread can explicitly yield to another thread.

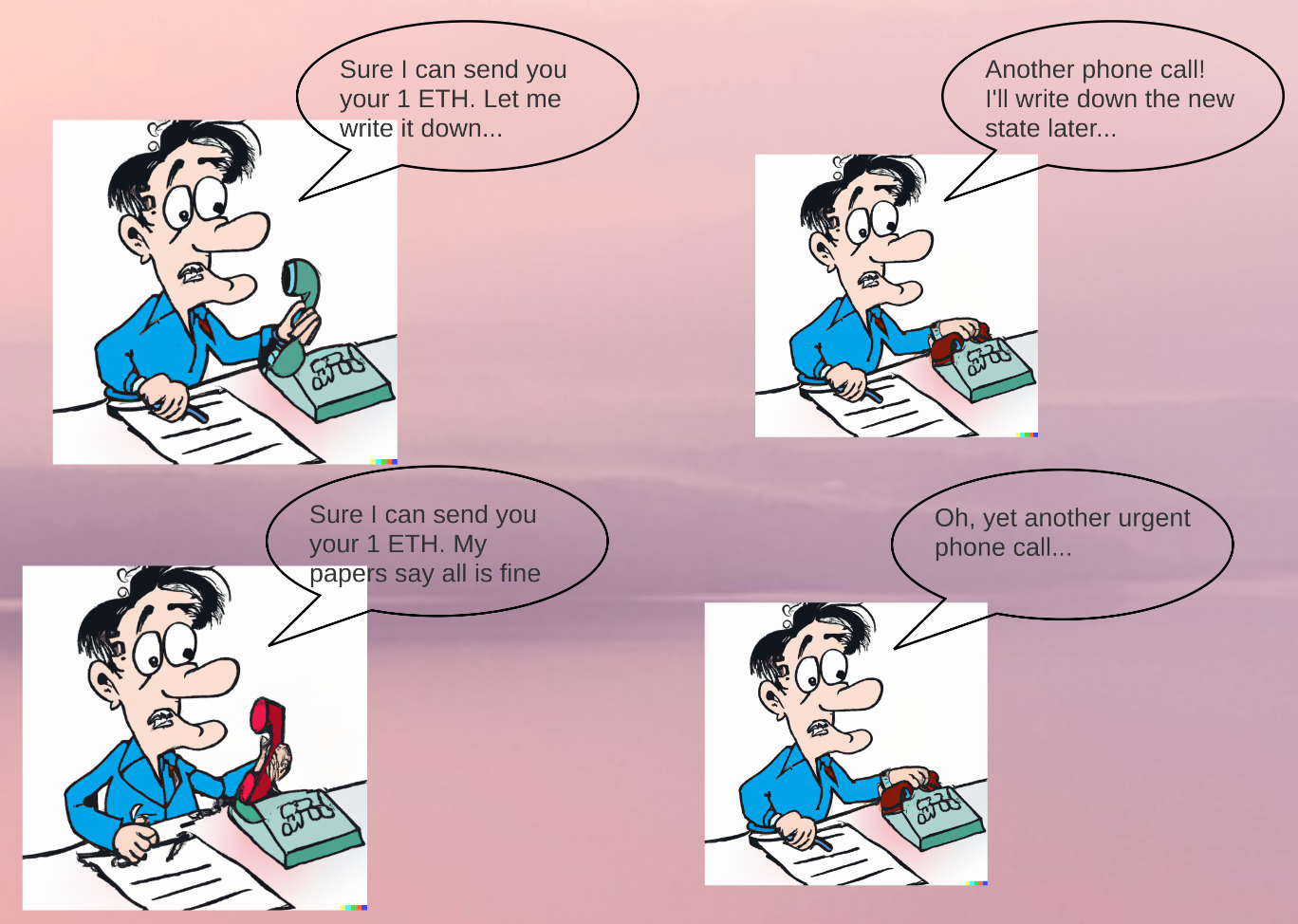

Exactly this concurrent aspect was responsible for one of the most notorious attacks - a reentrancy attack. The comic below explains the gist of the attack: asking a contract to send some funds, and then in handling of the sent funds calling again with the same ask. (For the attack to succeed, the victim contract needs to first send the asked funds, and only afterwards update its internal state.)

3. CosmWasm actor model

Knowing about the re-entrancy attack, the designers of CosmWasm decided to model their contracts as actors. That means there is no calling into other contracts, but only sending them messages, which are executed at some later point. In other words, a contract necessarily modifies its local state first, and only then yields control to other contracts (thus avoiding reentrancy-style attacks).

In that sense, CosmWasm’s execution model is very similar to the actor model as we saw it earlier. Unlike in that description, the order of message handling in CW is strictly determined.

Messages and their handling order

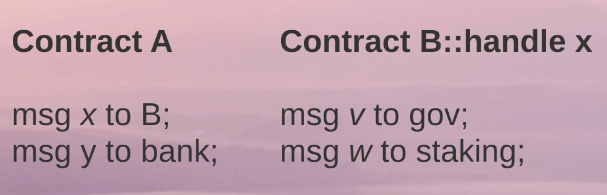

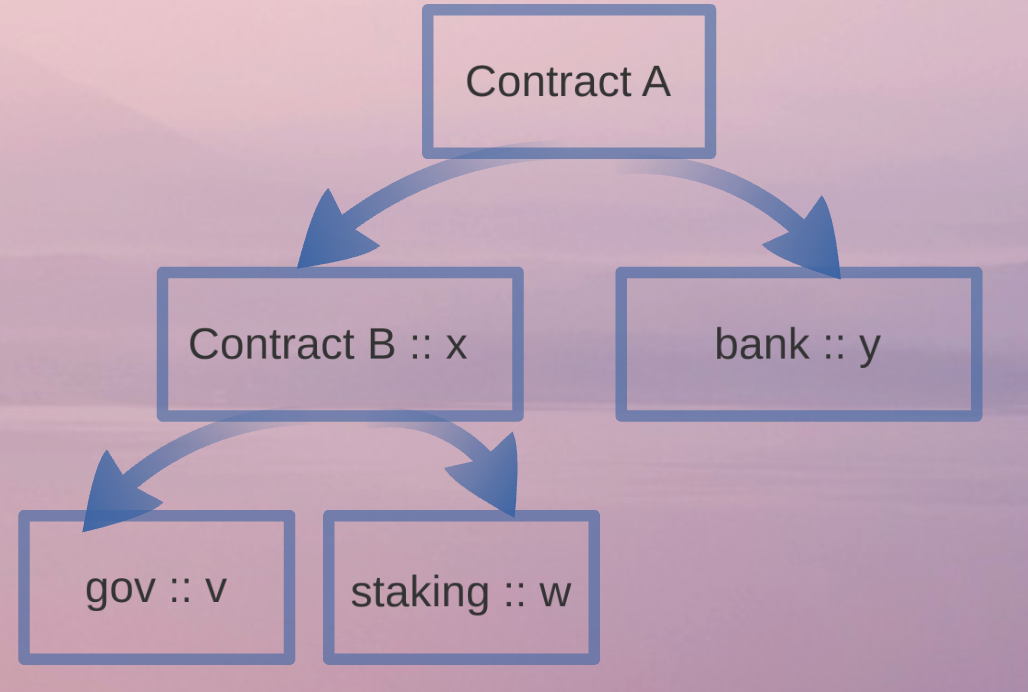

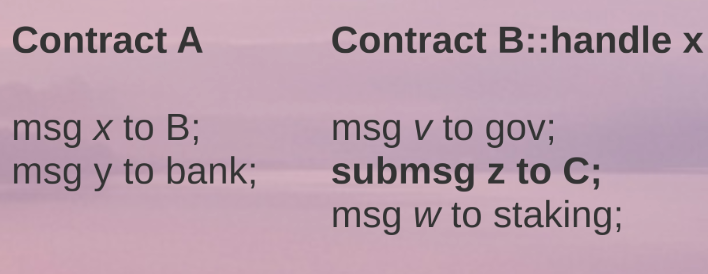

Take the following example, which shows contract A sending the message x to contract B, and how x is handled by B. (If you are not familiar with the Cosmos ecosystem, bank, gov, and staking are standard Cosmos modules. Their exact functioning is not important for the example.)

The order of executing messages is depth-first. Depicting the above code as a message-send graph, it looks like this:

Depth-first ordering of messages is as follows: A, B::x, gov::v, staking::w, bank::y.

Note the two (problematic) properties of this way of executing messages:

- If handling of any message fails, the whole transaction fails.

- There is no (direct) way to get a return value of a message.

To add a bit more flexibility to messages, CosmWasm introduced submessages. Submessages enable both handling failures and receiving return values (as responses to submessages).

Submessages, their handling order, and dealing with their failures

Submessages are just like messages, except that they carry a special ReplyOn label on them. The ReplyOn can have one of the following values: Always, Error, Success, and Never.

A message with the label ReplyOn:Error will on failure not revert the whole transaction, but a failure will be handled by the sender. The label ReplyOn:Success makes it easy for the sender to receive a return value from the receiver. The label ReplyOn:Always will give a chance to the sender to handle both the success and the failure, and the message with the ReplyOn:Never label is the same as the plain message - no response handling, and reverting the whole transaction upon failure. For more details on what gets handled when, have a look at this table in SEMANTICS.md.

The ordering of submessages is exactly like messages - depth first, with the addition that handling of responses is treated like a message immediately sent in an opposite direction. (Interestingly, this ordering rule was not always that way and is therefore a common point of confusion - see the PR#1922.)

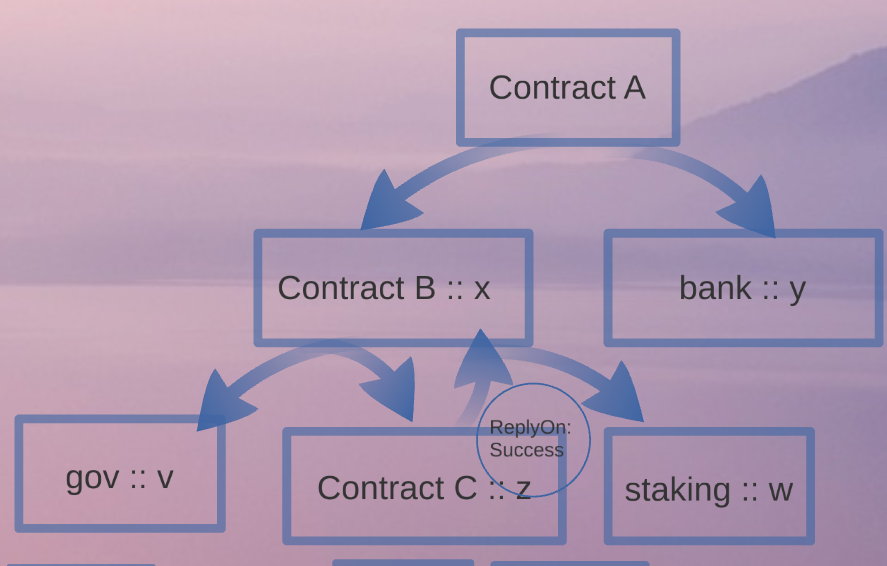

Consider an example similar to the previous one - except that now there is one submessage sent from contract B to contract C.

Its tree-like representation looks like this:

Then, the order of message handling is the following: A, B::x, gov::v, C::z, reply(C->B), staking::w, bank::y. Here, the reply is called if and only if C’s handling of the message z returns success.

Handling of submessage responses and failures

After the submessage handling is finished, the caller gets a chance to handle the result (if the appropriate ReplyOn label is present) in its reply function. One important point about reply is that its return value overwrites the return value of the original caller. Quoting from SEMANTICS.md:

“If

replyreturnsdata: Some(value)in theResponseobject, we will overwrite thedatafield returned by the caller. That is, ifexecutereturnsdata: Some(b"first thought")and thereply(with all the extra information it is privy to) returnsdata: Some(b"better idea"), then this will be returned to the caller ofexecute(either the client or another transaction), just as if the original execute [had] returneddata: Some(b"better idea")”

If there are multiple submessages, the last one overwrites all the previous ones.

TL;DR

CosmWasm’s design of contracts as actors is a neat idea that makes it easier to create safe contracts. One still needs to be aware of the order of message handling and the semantics of responses to use the full power of messages and submessages.

Hope you enjoyed this post, and let me know if something could be improved or needs to be corrected.