Blockers and Unblockers: two kinds of AI coding assistants

“The worst business idea: AI that calls you on your bullshit… That’s really good” - Paul Bloom (video)

AI coding assistants have been extremely helpful, both in my experience and talking to colleagues and friends. Everybody got a superpower - those who used to be good, now are even better; those who didn’t know much, now have direct access to knowledge; those who were not able to program at all, now scrap their first working programs.

Most commonly, AI assistants unblock us on the way of turning ideas into code. They help avoid context switching needed to look up the documentation of the API we are using, or to summarize pages of forum discussions.1

Out there in the wild, however, there is a complementary kind of AI coding assistant: those assistants block us from implementing bad ideas. They are perhaps less attractive, since they do not open new doors for us. However, they are equally useful: stopping us from taking a wrong path and getting lost on it.

Those blocking assistants have been around for some time already, and were developed as part of the formal methods project. The stated goal of the project is to build tools that can check if the program is doing what it is supposed to do. As a (partly unintentional) side-effect, we got programming and thinking assistants2.

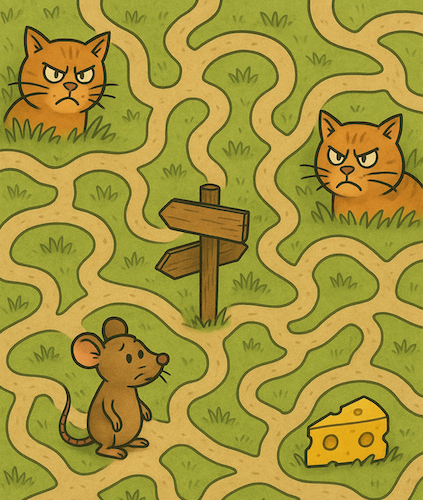

Assume we are to implement a new algorithm. We may first sketch the idea on paper, and then go ahead and describe the idea in a specification language. The assistant then reads this description and warns us about the properties that do not hold in our design. We can iterate on this step until the assistant cannot find any more problems in it. The whole process happens before the implementation has even started, thus saving us a lot of time.3

Unfortunately, there are some unsatisfactory parts of the workflow:

- We need to decide on the level of abstraction at which we describe the idea to the assistant. If we make a wrong decision here, we may still miss a problem.

- We need to put extra effort to use a specification language. Additionally, since not everybody knows the specification language we used, the final specification will not be universally understood.4

- The analogy with unblocking coding assistants is not complete: the described tools are really “pre-coding assistants” or “design assistants”. This makes them significantly more important, but they feel less magical.

For those reasons, while unblocking assistants are getting ever more popular, the blocking assistants still remain a niche topic. Considering the superpower they give to their users, it is worth incorporating them into our programming practice, and addressing the shortcomings they have.

It is indeed one of the most interesting topics to work on in the coming years.

Notes:

1: A common objection is that this ‘gets the job done’ but hinders learning. That may be true, but the same thing likely happened in the past as well, when we were not in the right frame of mind: sometimes we just want to find a solution to a side-problem that’s blocking our main ideas; other times we want to dive deeper and learn more.

2: Some languages to interact with blocking assistant are TLA+, Lean, FizzBee, Promela, or Quint

3: Compare this to the workflow when not using blocker assistants:

- We write the idea on paper (or a markdown page)

- We think hard about it, get reviews from colleagues, in an attempt to spot problems

- We start implementing it (or even finish the implementation), and then one of the tests reveals a subtle design issue. Now we are back to square one.

4: The problem of the specification language not being a good medium for human-to-human communication is something my colleagues at Informal Systems and I are thinking about and exploring. Our first attempts focus on using Literate Specifications